Literary Lode: Living on the Edge

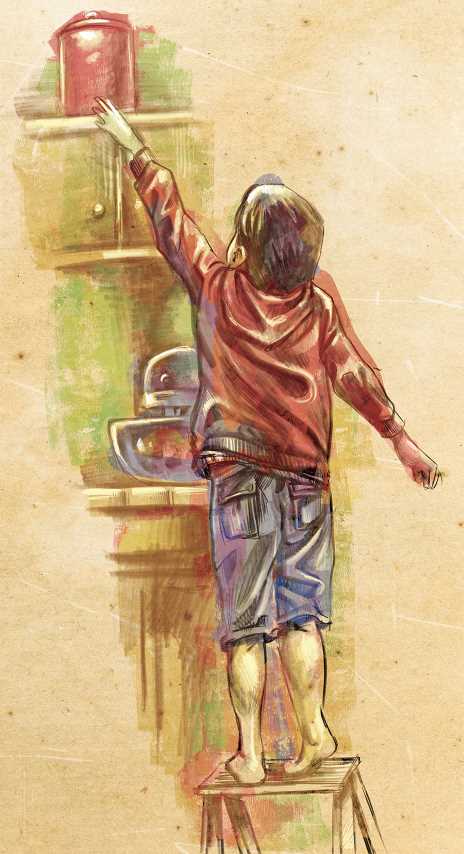

Maybe it all started with a rickety metal stepladder and a red tin of cookies, much too high to reach for a four-year old, but close enough in a toddler’s mind to give it a try. Danny managed to grab two of the sugary rounds before he toppled back, smashing both his head and the cookies onto the tile floor. Though he had only a smidgen of memory of what followed, his mother described it to him on his tenth birthday, serving up the same cookies as she related her scream, the rush to the ER, and two weeks in intensive care, not knowing if there was serious, permanent brain damage.

Maybe it all started with a rickety metal stepladder and a red tin of cookies, much too high to reach for a four-year old, but close enough in a toddler’s mind to give it a try. Danny managed to grab two of the sugary rounds before he toppled back, smashing both his head and the cookies onto the tile floor. Though he had only a smidgen of memory of what followed, his mother described it to him on his tenth birthday, serving up the same cookies as she related her scream, the rush to the ER, and two weeks in intensive care, not knowing if there was serious, permanent brain damage.

There wasn’t. Well, not exactly.

It wasn’t long after that birthday that Danny went to a swim party at a friend’s house and, on a dare of course, climbed up the high dive and walked onto the board where he teetered for a moment before bursting into tears, hugging the board tightly and crawling slowly, scraping himself back to the platform, where he refused to step down until his mother climbed the pool ladder to retrieve him. Later, in bed that night, as he relived the terror, his hands and feet grew clammy-moist, and his stomach churned and twisted on itself until he stumbled to the bathroom and let loose with the chicken, peas and mashed potatoes he had for dinner.

There had been other episodes throughout his teen years and twenties. Never again high dives, but striking, blinding fear when he tried working a mid-rise construction job in Bozeman, anywhere above the second floor, or when he attempted to visit the top of the Hancock building in Chicago, or when he tried to hike the South Rim Trail beyond Artist Point in Yellowstone, along the gaping, hungry maw of the river canyon. Lately, he realized that things had gotten worse when Maddy shared a photo of her ice-climb that a friend had taken from the top of Hyalite Falls. There was Maddy far below, ice-axe in hand, the bright shimmer of freeze growing all the way from the canyon floor to the edge, where someone with a camera leaned over for the shot. Just the sight of it made his head spin. His hands trembled as he pushed the pic back into Maddy’s hand.

Soon after that he went to a psychiatrist and paid an unnecessarily big bill so that someone could tell him what he already knew.

Daniel, Dr. Abrams said, there is no question in my mind that you have somehow developed a severe case of acrophobia.. Phobias can be caused by stressful events, like the one from your childhood, which could have induced a fear of falling. This is certainly related to that, and there only limited options to help you, I’m afraid.

Abrams paused, looking over the tops of his glasses, fuzzy caterpillar eyebrows folding over the frame.

I can prescribe something like Seromycin, but the only thing that really works with phobias of all kinds is exposure therapy. You face your fear in small ways at first, then increase your exposure to the fear until you can at least manage the symptoms if not the terror. The catch, I suppose, is that you have to do it yourself.

Yourself. That is what he remembered from the session, and he had been working on exposure therapy steadily for the last three years, working on his fear of falling. He started with photos from the internet—daredevil, Mohawk ironworkers atop New York skyscrapers from the ‘30s and 40’s, pics of crazies wing-suiting from bridges and building tops; and then moved on from simply crazy to the pure video insanity of Philippe Petit’s 1974 Man-on-Wire tightrope stroll across the twin towers. The possibility of sure death from a fall was beyond comprehension; but, after several viewings of the documentary, it helped move him onto more immediate and challenging exposures: the lowest diving board at the health club, rooftop breweries, where the beer helped settle him, and repeated walks to the top of the university stadium stairs to peer over the edge, guard-rail securely in place.

Things had been getting better, he had to admit. The vertigo, the nausea had receded. So much so, that he soon was able to walk the trail along Yellowstone Canyon without completely losing it, as long as he did not venture toward the very edge. Because it was at the edge where things could go completely wrong, horribly wrong. It was on the trail when he realized that it was not the height of things that unnerved him, but it was at the very edge, where almost anything could happen, anything at all. It was this realization which moved him to drive to north to Mt. Siyeh, moved him to the ultimate test of his exposure therapy.

Mt. Siyeh, Daniel knew, was the most accessible peak in Glacier National Park, and there was one photo in his internet desensitization of a point, an edge, far above Cracker Lake, where a sheer drop-off of 4000 feet would be his ultimate test, or his final undoing. Either he would conquer his fear, or his fear would conquer him. Decidedly. The route up would be both a climb and a scree-scramble in parts, but it was, no doubt, the ultimate test.

Really? Are you sure you want to do this, Maddy asked. “How ‘bout if I go with you?

Nope, Daniel replied, with an uneasy bluster of self-confidence. This is something I just have to do. I’ll be better on my own. You know, better concentration, less distraction. I just…just have to do this…myself.”

Which is how Daniel soon found himself far up the Preston Park Trail, the summit in view on an August day, bright and shiny as the proverbial penny, with only a few hours more until the ultimate test, which he hoped would conquer his fear forever. He understood it now, at least, which is why the hike up the mountain didn’t bother him despite the altitude, with no fear for occasional step-ups onto and over boulders and rocky crags. On the way up he had refined his theory. It was not the height of things that bothered him, it was rather the edge x height, a weird mathematical equation of some sort which equated to fear by proportion.

The cookie episode was buried somewhere in the synaptic cellar of his mind, but he still remembered the diving board at the birthday party and the panic-there was no other word for it-when he stepped to the edge, the water lapping below. There was something he couldn’t quite grasp about that day, though he felt it would come to him in one way or another.

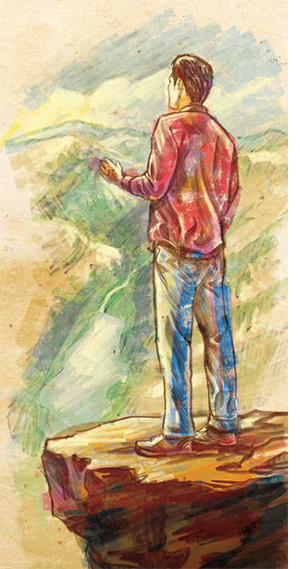

Only a few hundred feet from the top, from the overlook, Daniel stopped both to catch his breath and wait for his courage to catch-up. The steepness had lessened a bit. From his vantage point there was only rock-meets-sky, and beyond he could only imagine the emptiness, the soul-less void.  Each step was now more an effort of will than of physical ability. A small bank of clouds drifted in, and the wind began to pick-up, adding to his foreboding. Fifty steps. Thirty steps. Ten Steps. The edge.

Each step was now more an effort of will than of physical ability. A small bank of clouds drifted in, and the wind began to pick-up, adding to his foreboding. Fifty steps. Thirty steps. Ten Steps. The edge.

Daniel felt his legs shaking, though not from the effort, and he forced himself to look down, far down at Cracker Lake, so inviting, so peaceful, like the blue water at the bottom of the high dive. His mind twirled with anxiety, with rising panic, with a horrific realization as he found himself shuffling forward…

Daniel now understood that he was not afraid of falling. He was afraid of jumping.

Leave a Comment Here