Montana Media: the Ballad of Little Jo and Revisioning the West

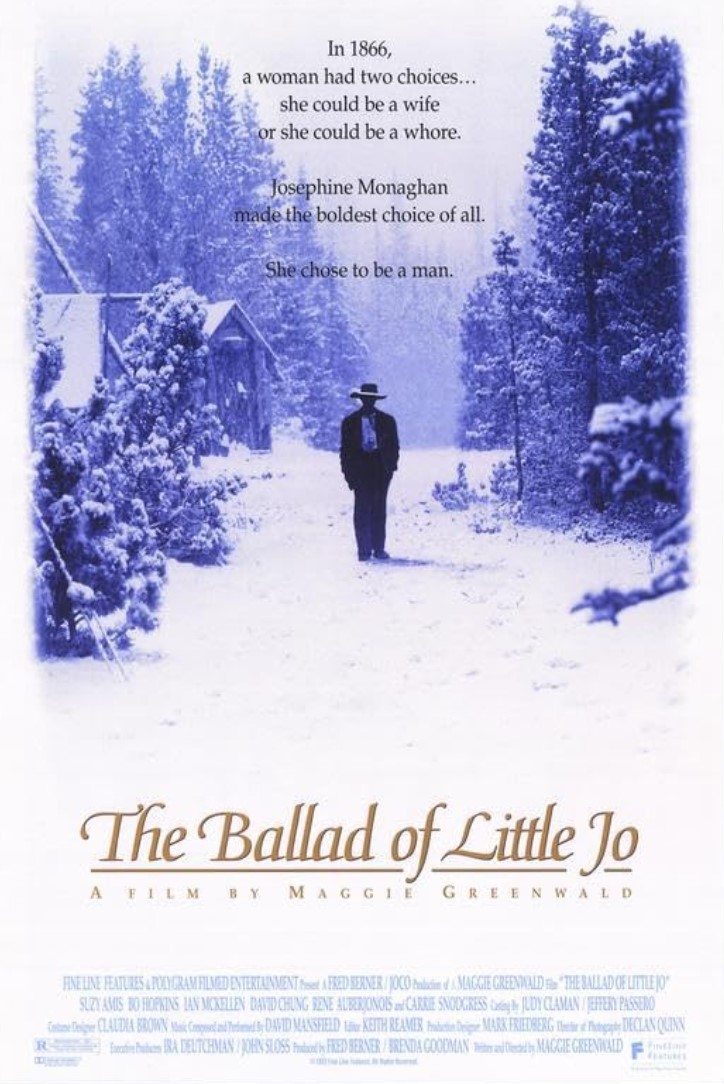

The storytelling tradition of a woman crossdressing to get through life has a robustly wide field of operation. Think of Mulan (both in its original Chinese legend and Disney movie renditions), or Yentl (both the original story by Isaac Bashevis Singer and the Barbra Streisand musical adaptation), not to mention the heroines of multiple Shakespeare comedies. The nineteenth century American West makes sense for such a story; there may be a multitude of dangers both from nature and man, yet there is also the space, literally and figuratively, for self-creation or re-invention. The Ballad of Little Jo (1993), written and directed by Maggie Greenwald, serves as a valuable example of this motif for Western cinema.

Though modest in production scale and unwilling to indulge in expected genre beats, the movie manages to tell a story of survival against gendered obstacles that feels, 31 years down the road, like an icebreaker for other Westerns, such as Scott Frank’s excellent miniseries Godless (2017) or Ana North’s 2021 novel Outlawed. Viewers coming to Little Jo expecting rip-snorting action will be primed for disappointment; knowing you’re in for a grit-flecked character study is more likely to result in a favorable impression. That the movie was filmed near Red Lodge, Montana on the border of the Custer National Forest grants its grittiness an additional layer of Treasure State genuineness.

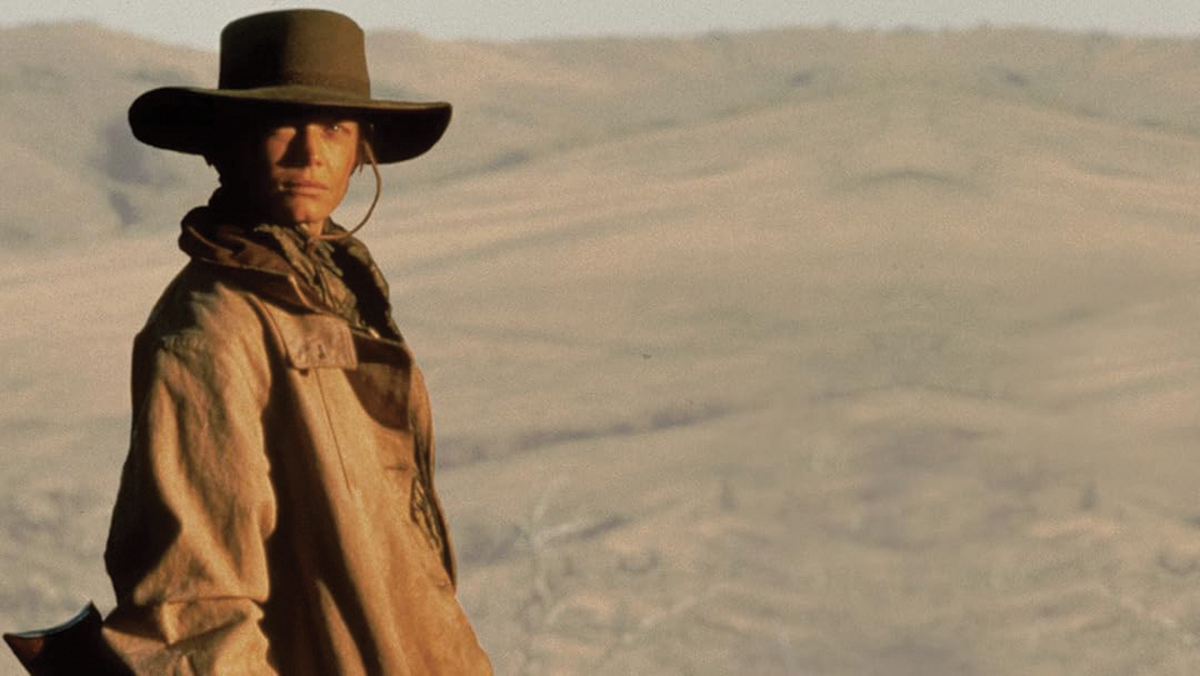

The film begins with Josephine Monaghan (Suzy Amis) being cast out by her well-to-do East Coast family after giving birth to a child out of wedlock. The reality of how precarious a single woman’s position is becomes distressingly clear after she narrowly escapes assault by a traveling salesman on the road. Realizing that disguise is her best defense, she slashes her own face, cuts her hair, buys some men’s duds from a general store, and becomes a young man named “Jo.” She ends up at a hardscrabble mining town called Ruby City, where she makes the acquaintance of Percy Corcoran (Ian McKellen, in his first American film), a displaced Englishman who at first serves as a friendly companion to Jo before his deep well of vicious misogyny becomes chillingly apparent. Eventually Jo is hired to tend sheep on the land owned by Frank Badger (Bo Hopkins, who will be well known to fans of Sam Peckinpah movies), later saving enough money to buy a small spread of her own. She even finds loving connection with a man, Tinman Wong (David Chung), who knows the truth and accepts her as a woman. But as the years roll by, can her secret remain hidden from the rest of the world?

The Ballad of Little Jo arrived right at the moment when the Western re-emerged after a protracted period of stagnation back into popular appeal. Kevin Costner’s Dances With Wolves (1990) and Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) both won the Best Picture Academy Award for their respective years of release, in addition to being commercially successful. Little Jo has far more in common with the latter; indeed, it would serve well as a companion piece to the Eastwood film in many ways. Both fall under the banner of “revisionist Westerns,” those films which take an intentionally unglamourous, if not always strictly historically accurate, stance toward the genre (they were all the rage during the 1970s). Both frankly acknowledge gendered violence, though to different ends. The brutal knife attack in the whorehouse in the opening scenes of Unforgiven sets up the Eastwood character’s mission of retributive bloodshed; in Little Jo the threat of sexual assault is the primary reason for the heroine’s disguise, and retribution isn’t on the table. There is one key scene involving a shooting but it doesn’t provide excitement or catharsis; the emphasis is on the pain of taking a life.

Another one of the revisionist aspects of the film’s script is its focus on characters who would be mere background figures in classic Western pictures. Significant attention is paid to the Slavic immigrants who populate Ruby City and the gradual process in which they become incorporated, however imperfectly, into the nascent community (there is a commonality here with Heaven’s Gate, another Montana-filmed Western). As was historically the case, a far greater degree of hostility is foisted upon the Chinese laborers who came to the American West. In the film, Jo first encounters Tinman when he is about to be lynched by a group of white men irate about the work the Chinese are supposedly taking away from them. The romantic relationship that develops between them could only occur due to the fact of their mutual outsider status. It is noteworthy how uncommon still in American movies it is to see interracial couples with an Asian man as the partner; in the early ’90s it was even more so. Those interested in going deeper into the story of the Chinese in Montana can look to Mark T. Johnson’s illuminating book The Middle Kingdom Under the Big Sky.

In an interview on the How the West Was Won podcast, director Maggie Greenwald stated why she envisioned the film as a Montana story: “I wanted to make a cool weather Western…this didn’t seem to me to be an Arizona or a New Mexico kind of story.” Though the shooting schedule did originally plan to film in other states (including, funnily enough, in Arizona), these plans were scrapped after arriving in Red Lodge and discovering the area fit with all the production requirements. Shooting begun in the summer, but snow still hit, as is ever the possibility in Montana. In a move of admirable improvisation, Greenwald incorporated the snow into the film, introducing a changing-of-the-seasons element that hadn’t necessarily been intended in the script. The weather curveball, by serendipity, fit into the rhythm of the final product.

Greenwald is an unsung example of what an independent film director can achieve, even with constraints of funding and resources. Her resume includes The Kill-Off (1987), a noir-thriller adapted from a book by Jim Thompson; Songcatcher (2000), a beautiful humanist period drama about folksong collection in Appalachia; and Sophie and the Rising Sun (2016), another period piece centering on community outsiders and forbidden love. Even though it didn’t do well commercially on its original release, The Ballad of Little Jo is arguably her most influential work as a filmmaker; its quiet example of what a Montana story can be has proved durable, at least among Western aficionados and those who might be dismissive of them. Like women in the West, it may have been overlooked, yet has stood its ground and endured.

Leave a Comment Here