Paradise By the Carton: The Legacy of the Marlboro Ranch

What if I told you there existed a place in Montana, a place where the myth of the Old West was made real, where millions of ordinary folks around the world wanted to go?

A place as magical as Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory, where all your cowboy fantasies can come true? What if I told you no amount of money could buy your way in, only your loyalty? For many who dreamed of coming to Montana, nestled in the foothills of the Crazy Mountains, Marlboro Ranch was that place.

And all you had to do to get there was to smoke a lifetime's worth of cigarettes.

When cigarette ads were banned from TV and radio in 1971, Philip Morris, makers of Marlboro, faced a marketing dilemma. The ban had effectively cut off their primary way of reaching large swaths of the American public. Though ads would continue in print media like magazines, newspapers—and those ubiquitous, oversized billboards that graced highways from Boston to Miles City—it seemed the writing was already on the wall. Further restrictions came in 1999, when the advertising ban included public transit, paid product placement, even advertising at concert venues and sponsorships of sporting events like NASCAR.

As cigarettes became harder to advertise, tobacco companies needed to find other ways to reach new customers and to reward their most loyal ones. Anyone around in the 1990s knew somebody—a neighbor, a coworker, an uncle—who collected “miles” (the bar codes) from packs of Marlboro cigarettes. In this era of branded cowboy merch, the “miles” could get you everything from hoodies to leather backpacks, camp stoves to tents, and if you were patient enough (or a dedicated enough smoker) even something called a Fuji folding bike, though at 2,200 “miles” that comes out to nearly 500 packs of cigarettes.

Marlboro “miles” and the accompanying Sears catalog of merchandising was only a stopgap for Philip Morris’ more ambitious plan. After Marlboro Man was forcibly retired in 1999, a 45-year campaign widely considered the most successful in advertising history, what Philip Morris wanted most was a way to reconnect directly with consumers. Their radio and TV ads depicting Marlboro’s version of the mythologized American West had already been banned for a generation. Now, with even billboards, a thing of the past, Marlboro Country and the Marlboro Man seemed destined to become forgotten.

But if Marlboro Country couldn’t be brought to their customers, what if Philip Morris brought their customers to Marlboro Country?

Every year, starting in 1999 and ending with the Covid-19 pandemic, Philip Morris would invite about 350 people out to Montana for a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Travel costs, lodging, meals—everything was paid for. Dubbed the “Disneyland for smokers,” a better analogy for the Marlboro Ranch experience might be 1971’s Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, starring Gene Wilder in the titular role. Unlike Yellowstone Club, where exclusivity depends on net worth, Marlboro Ranch didn’t come with any financial stipulations. You didn’t have to be rich or famous or know anybody to get in. For Philip Morris, the ranch’s exclusivity equated to brand loyalty. Like in the original Gene Wilder film, the only way to gain access was by invitation. Which meant only the recipients of a Golden Ticket—five were hidden in Wonka’s namesake chocolate bars—got a chance to tour his magical factory.

Every year, starting in 1999 and ending with the Covid-19 pandemic, Philip Morris would invite about 350 people out to Montana for a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Travel costs, lodging, meals—everything was paid for. Dubbed the “Disneyland for smokers,” a better analogy for the Marlboro Ranch experience might be 1971’s Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, starring Gene Wilder in the titular role. Unlike Yellowstone Club, where exclusivity depends on net worth, Marlboro Ranch didn’t come with any financial stipulations. You didn’t have to be rich or famous or know anybody to get in. For Philip Morris, the ranch’s exclusivity equated to brand loyalty. Like in the original Gene Wilder film, the only way to gain access was by invitation. Which meant only the recipients of a Golden Ticket—five were hidden in Wonka’s namesake chocolate bars—got a chance to tour his magical factory.

Wonka’s stroke of genius was his viral marketing plan. To improve their chances at a Golden Ticket, children around the world were encouraged to eat as many Wonka bars as possible. Likewise, for Philip Morris, each Marlboro pack you smoked increased the likelihood of you receiving an invitation to Marlboro Ranch, what became a lifelong goal for many customers of the brand. Although the Wonka-like sweepstakes wasn’t the only way to get to Marlboro Country, how Philip Morris determined their most brand loyal has always remained a mystery. But why a dude ranch for smokers, and more importantly, why here in Montana?

Forty-five years in the making, Marlboro Ranch was the final iteration, the logical conclusion of Philip Morris’ iconic Marlboro Man ad campaign that started in 1954. To fully realize the Marlboro Country that had only existed on TV and billboards for customers, they had to leave a good first impression. Philip Morris, who knew advertising better than just about anyone in the business, didn’t disappoint. For the lucky and chosen few, it was the adventure of a lifetime.

As soon as you land in Bozeman, your motley crew of city slickers would motorcoach the short way to Clyde Park. Even before you arrive at the ranch, look out your window and you might glimpse several men riding flank, galloping alongside your motorcoach in full cowboy regalia, head to toe, in all their glory, like epic riders of a John Ford western. Chances are, the theme to The Magnificent Seven soundtracks the whole surreal scene to Marlboro Ranch; in the 1960s, Philip Morris had licensed the song as part of their Marlboro Country ad campaign.

As soon as you land in Bozeman, your motley crew of city slickers would motorcoach the short way to Clyde Park. Even before you arrive at the ranch, look out your window and you might glimpse several men riding flank, galloping alongside your motorcoach in full cowboy regalia, head to toe, in all their glory, like epic riders of a John Ford western. Chances are, the theme to The Magnificent Seven soundtracks the whole surreal scene to Marlboro Ranch; in the 1960s, Philip Morris had licensed the song as part of their Marlboro Country ad campaign.

During the wallpaper-licking scene in Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, Veruca Salt, one of the Golden Ticket winners, tells Wonka that nobody’s heard of a “snozzberry,” implying that Wonka just made that up. Wonka leans forward, lowers his voice, and responds with the cryptic line: “We are the music makers, and we are the dreamers of dreams.” Wonka knows what Veruca Salt doesn’t—that this guided group tour she and the others are on has little to do with “snozzberries,” or even them, the Golden Ticket winners, and everything to do with Wonka himself and the success of the Wonka brand.

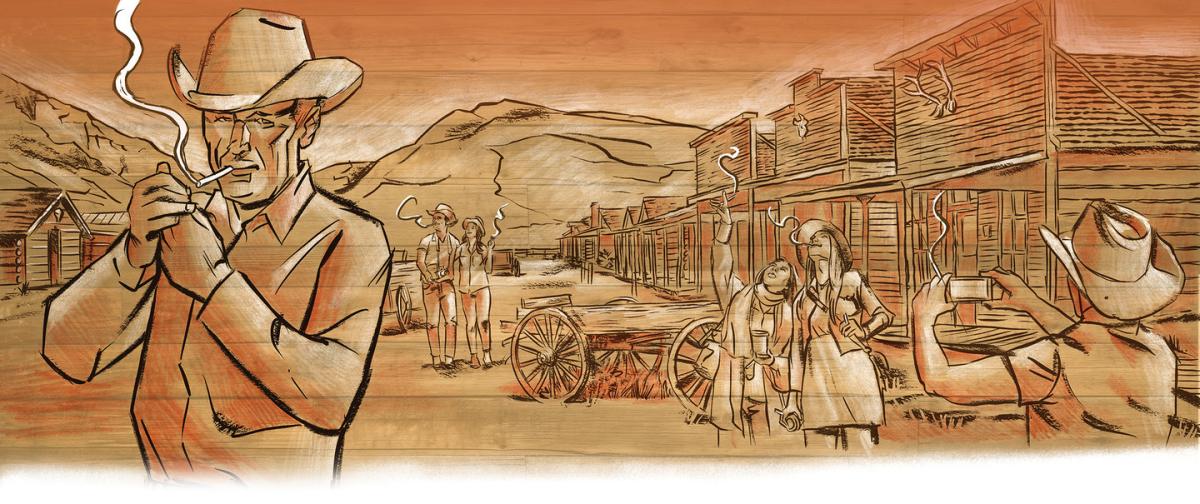

Until its closure, the reason Marlboro Ranch existed at all was because of brand loyalists, and Philip Morris was just returning the favor. Staffed and open year-round, the working ranch provided activities for every season. Over a typical four-day stay, fare included guided backcountry treks, fly-fishing, skeet shooting, along with horseback riding, and on warm summer nights—if you were lucky—getting grub from an honest-to-goodness chuckwagon parked outside your hotel. You could drink and dance the night away, learn how to twirl a rope, or cozy up in one of several lodges along the ranch’s main drag. Also provided were less well-known Old West activities like mountain biking, ziplining, and taking a Hummer off-road. In the winter there was snowmobiling, dog sledding, and more ziplining (but only in the Activity Barn). And if you really got what it took to be a cowboy and wanted a hog-killin’ time, then maybe, just maybe they’d let a greenhorn like you ride along and help drive their herd of cattle home.

During the Marlboro era, even while entertaining guests, the ranch remained a working ranch. Maybe this had a lot to do with how immersive the experience was for visitors. Two dozen buildings still stand, many restored after Philip Morris purchased the property, and everything you’d expect to find in a typical cowboy western can be found here: lodging at the Crystal Palace Hotel and the saloon next door; a post office and bank, the Sheriff’s Office a stone’s throw away across the street. There’s Chin’s Laundry (still used by staff for the same purpose) and a General Store stocked with candy, jerky, other snacks and treats, though you can’t buy any of it, because money—like in Wonka’s factory—has no value here. True to the experience Willy Wonka curated for his guests, allowing them to indulge in fountains and rivers of chocolate to their heart’s desire, everything in the General Store—at Marlboro Ranch—is absolutely free. Other buildings include a livery, Shawmut Lodge and Dancing Bear Lodge, the unimaginatively named Activity Barn, a riding barn, a firehouse, and even a barbershop.

Occasionally, Philip Morris invited loyal customers back to Marlboro Country for a second visit. Out of the blue, around November, invitation calls would go out to select guests for a New Year’s Eve adventure, all paid for, of course, by Philip Morris. Along with the usual list of winter activities, these special timed events gave an opportunity to curate an even more personalized experience, going so far as hiring photographers and videographers from National Geographic to document their guests doing things they wouldn’t normally do—like dog sledding.

For the event “Photography Experience,” professional photographers from the Smithsonian would be brought in to teach guests how to properly use a camera. Afterward, guests were sent out to practice the techniques. There was also a party and a countdown, of course, to ring in the New Year. And yes, even fireworks.

In June 2021, Altria Group, parent company of Philip Morris USA, quietly sold their 18,000-acre property just east of Clyde Park for an undisclosed amount. The buyer was private equity firm Lone Mountain Land Co., itself a subsidiary of CrossHarbor Capital Partners. Ordinary Montanans, however, might know the property’s new owners by their outsized presence elsewhere in the state—the Yellowstone Club in Big Sky, whose members include NFL quarterback Tom Brady, Microsoft founder Bill Gates, and many Hollywood A-listers like Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez. Deposits to get on a waitlist cost $400,000; purchasing property, a requirement for membership, start at $3.5 million. You can't help but think that this is the kale and Ozempic crowd we're talking about, not leather and tobacco. It's probably pretty tough to bum a smoke up there.

Putting aside how we feel about megalomaniacal cigarette companies, the Marlboro Ranch allowed millions of ordinary folks dream big dreams. Though no less exclusive than Yellowstone Club, it played a vastly different role and served a significantly different demographic. They were usually middle to lower-class, blue-collar smokers enamored with a vanishing West. preferred cowboy swagger over glitz and glamor, a black felt stockman over an evening gown. They longed for a way of life that no longer existed and in some cases never had, a Montana more mythical than real, but one that stirred imaginations that had been raised on Disney's Davey Crockett TV show and John Wayne matinees. They smoked their Marlboros and repeated their mantra: any day now I will get a call, and then I'll know it's my turn to go.

And for those loyal enough, determined enough, those who rode for their brand, coming to Montana, the real Marlboro Country, fulfilled a lifelong dream.

Here they found paradise. Paradise by the carton-full.