James J. Hill, Empire Builder

RAGS TO RICHES

A contemporary of the infamous robber barons who ruled industry at the turn of the 20th century, Hill's childhood held no indication of a success. Born to a poor family in what is now Ontario, Hill's father died when he was 14, prompting him to assume adult responsibilities. At 18, he moved to America, eventually landing in St. Paul, the northernmost port along the Mississippi River, where he used his limited education, but keen mind, as a mud clerk for the steamboat industry.

While there are individuals of this era who share a similar beginning, circumstances aligned to launch his path. When many of his business superiors left for the Civil War, a childhood archery accident that left him blinded in his right eye prevented him from volunteering. The U.S. Army was not equipped for left-shooting soldiers. As a result, he quickly rose within the industry, all the while developing an excellent reputation.

"It required an attention to detail-oriented brain, and he had this kind of mind. He was very bright. There are things that set him apart," says Alex Weston, lead researcher and program associate at the James J. Hill House in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Through his business connections, Hill pulled together investors to purchase the bankrupt St. Paul and Pacific Railroad in Minnesota along the Red River, a highly productive farming area depending upon an unreliable steamboat system. With this successful venture, he encouraged his partners to think bigger. There were already railroads, but Hill believed he could make them better.

THE RISE AND FALL OF RAILROADS

Before Hill stepped into the picture, the federal government created the Pacific Railway Act in 1862 encouraging the development of transcontinental railroads through land grants and direct subsidies paid by the mile of track constructed.

"It was the perfect storm to attract true robber barons," says Weston. "'Let's built this as cheaply as possible and longer than we need it.' These railroads are treated by investors as get rich quick schemes."

Using untreated ties, cheap steel rails, and impractical, winding routes, failure was almost guaranteed. Weston says, "Hill had a clear-eyed understanding of what the railroads did wrong."

Instead of depending upon the government for free land and payments, he developed industries along the route to support his expanding empire. Yet, although he didn't benefit from the handouts, government policies directly influenced his business practices.

In 1862 the Homestead Act offered 160 acres of free land to those who improved it within five years. It also allowed speculators, such as the railroad, to purchase land at $1.25 per acre and sell it to those wishing to stake their claim in this exciting new region. Settling the West in this manner was partly due to the prospect of quickly ending the Civil War. "If the Union can stake a claim in the West, the South will be demoralized," said Weston, particularly because so many Southerners were not plantation owners.

The grim reality was that Indigenous people already resided in this area sought by homesteaders, but it didn't take the federal government long to find a way around the situation. "(In 1887) Congress universally ended previous treaties," says Weston. He explains that the General Allotment Act, also called the Dawes Act, declared that on the reservations, any land in excess of Native need could be homesteaded. In practical terms, if a teepee wasn't sitting there, it was often offered as a homestead or sold to a speculator, who set down new tracks or sold parcels to immigrants.

While Hill purchased land directly from the tribes in many instances, Weston says, "Going through native lands is a source of Hill's wealth. The federal Indian policy, at that time, is why the railroads were so successful.

BRINGING IN HOMESTEADERS

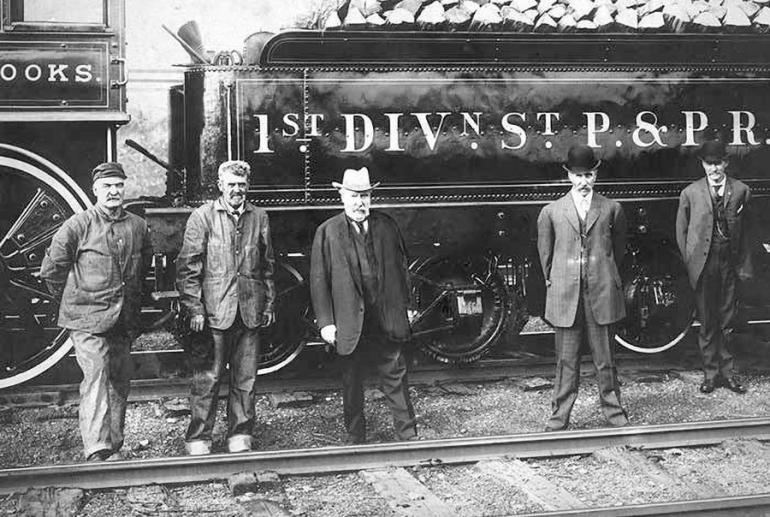

After the success of the St. Paul and Pacific, which was reorganized in 1879 as the St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railway Company, the Manitoba line headed west, making the most of the potential resources.

Weston says Hill firmly believed that "Agriculture is the reason the land has value. He was interested in a sustainable business that would grow more profitable because it was a good idea," not because the government was writing a check to do so. To encourage family farms, Hill's railroad actively promoted homesteading dreams to European immigrants, and the population of Montana grew 300 percent between 1890 and 1920.

A visionary in many respects, Hill stressed the importance of "proper utilization of the soil," even offering the keynote presentation during President Theodore Roosevelt's conservation commission at the White House. Weston says, "He didn't approach nature with just a 'take' attitude. It was a radical departure from the attitudes at the time."

As homesteaders spilled into Montana, Hill's passion for agriculture lent support to their efforts. Weston notes that Hill owned hobby farms in Minnesota where he bred cattle and crops that grew well in northern climates and shared these with the homesteaders. "He really saw himself as a great benefactor of farmers," Weston says. Unfortunately, this did not play out in the long term as many farmers blamed Hill for their failures during the disastrous time around 1919 when drought, wire worms and grasshoppers decimated crops.

CREATING THE FOUNDATION FOR AN EMPIRE

Despite his connection with those who work the land, Hill's strength was his vision for integrated industries considering not only farming and ranching, but integrated industries including farming and ranching, along with mining, and eventually tourism. "He had a comprehensive view of these resources," explains Weston. Employing multiple systems was critical for creating a solid foundation beneath his railroad, making it immune from the bankruptcies that plagued other lines.

Throughout these endeavors, Hill had his thumb on the pulse of every process, earning him the reputation of a micromanager with his belief, "It pays to be where the money is being spent." Every season he traveled in his private car examining tracks and noting failings along the rail line, ranging from structural defects to whether a depot was not well-kept.

During the flurry of activity of the constant expansion, Hill knew many of the names of the men and was known to pick up a tool and fill in while a worker grabbed a cup of coffee. While he respected those who toiled for him, he was a task master, pushing the men and routinely firing them if their work did not meet his expectations.

In 1884, Hill visited Paris Gibson, a business associate from St. Paul who was plotting the new town of Great Falls. While standing on the edge of the Missouri River, Hill recognized the potential of the region. In short order, he brought together other savvy investors, forming the Great Falls Water Power & Townsite Company, along with creating an alliance with Marcus Daly, owner of the Anaconda Mining Company in Butte. With copper dominating the scene, Hill built the Central Montana Railway in 1886 from Butte to Great Falls, eventually connecting it to the St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railway, which became the Great Northern Railroad in September 1889.

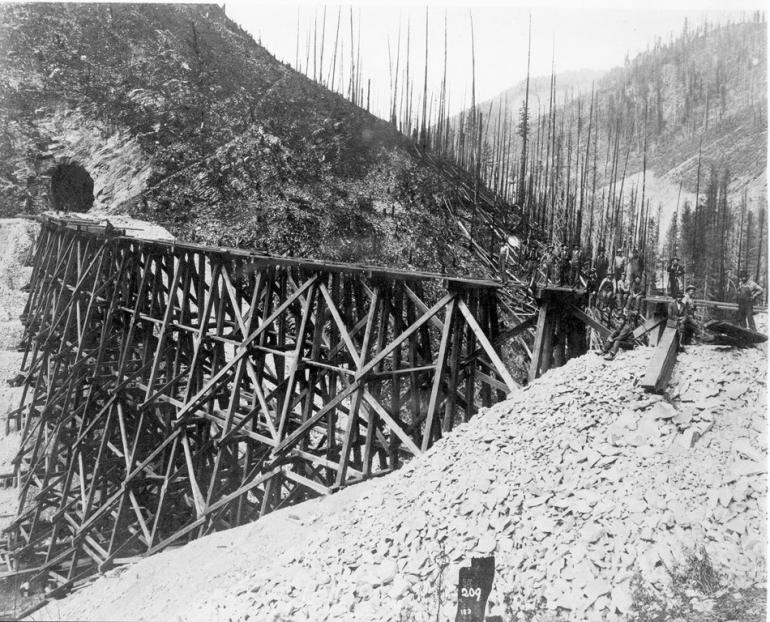

Even with this boundless potential in central Montana, his westward-bound rail line was roughly 700 miles east of Great Falls. Beginning in the spring of 1887, 8,000 men graded the route, and hundreds of track layers and timber workers laid the rails at a feverish pace. In August, they celebrated a single-day record of 8.3 miles of track set, and by mid-October, the line miraculously reached Great Falls.

With the creation of the first hydroelectric facility in 1890, at the current location of the Black Eagle Dam, there was power for the Boston & Montana Consolidated Copper and Silver Mining Company smelter in 1892 to process the ore from Butte. The coal mines in Sand Coulee, roughly 18 miles outside of Great Falls, produced upwards of 2,000 tons of coal each week to fuel the trains. Everything worked toward the benefit of the Great Northern Railroad.

PUSHING WEST

After completion of this monumental task of building the section in record time, Hill set his sights on reaching the West Coast. Desiring a less steep path over the Rocky Mountains, Hill employed locating engineer John F. Stevens to follow up on rumors of a lower elevation pass. "Hill thought the builder of the Northern Pacific picked the wrong spot," says Weston.

Setting off in December 1889, Stevens and a Flathead guide headed toward the elusive pass from the east, trying to locate the headwaters of the Marias River. With the guide staying behind at one point, Stevens continued alone in the brutal conditions, ultimately pinpointing the location. With temperatures plummeting, he could not build a fire because of the deep snow; instead, Stevens walked back and forth throughout the night to keep from freezing. The thermometer in the valley read -40 degrees F.

Arriving in Seattle by January 1893, Hill had his transcontinental railroad, along with an integrated system of industries along the way. "This is the era when monopoly was not just a board game," says Weston. "By 1905, there was not a railroad going through Montana that was not run by Hill." "Empire Builder" was a fitting title, even though he remained a polarizing figure, vacillating between ruthless businessman and someone who provided countless opportunities.

BEAUTIFUL NEW HORIZON

Appreciating the outdoors throughout his life, it wasn't a stretch for Hill to recognize the value of the landscape. Weston notes the national park movement began taking shape in the early 1900s with the Northern Pacific and the Union Pacific Railroads building facilities in Yellowstone National Park.

For years, it was customary for those with means to visit the great capitals of Europe, but Weston says, "There was this new idea to promote what we have that Europe doesn't." And it didn't take long for the Great Northern to incorporate it as their slogan.

In 1907 Hill turned the company over to his son, Louis Hill, who shared his father's hands-on approach. The younger Hill immediately began negotiations with the federal government, and with the strong support of influential conservationist George Bird Grinnell, President Taft signed the legislation making Glacier the tenth national park on May 11, 1910.

Belton Chalets, built in 1910-1911, were the first accommodations built by the Great Northern, followed by Glacier Park Lodge, Many Glacier Hotel, the Prince of Wales, and eight other chalets, including the Granite Park and Sperry Chalets. Both James and Louis Hill viewed these accomplishments as legacies for future generations with visitors enjoying them to this day.

POLARIZING FIGURE

"During his life he's both celebrated and vilified," says Weston. With boundless energy and vision, Hill created an empire that reached across America, and ultimately the Pacific Ocean, opening trade routes to Japan, once again for the benefit of farmers and his railroad.

Although Hill stepped back to allow Louis to take the lead, he didn't officially retire until 1912 at the age of 73, yet he remained busy by starting several banks and frequently speaking at events. Death was the only thing that could slow him down. Hill suffered with an infection on his thigh, yet still worked in bed until it spread beyond hope. Surrounded by his beloved wife, Mary, and nine children, he passed away on May 29, 1916.

To give respect to this influential individual, this was the first time flags were flown at half-mast for a private citizen in Minnesota, and on the day of his funeral, schools, banks and other public institutions closed. At the time of his funeral, according to The New York Times, "Every wheel on the three great railroad systems he controlled stopped turning for five minutes at 2 o'clock this afternoon." Bells and whistles signaled all along the Great Northern line while the engines were cut on every train and steamship.

Fittingly, the year of his passing was also the height of the railroad, and as automobiles soon dominated the scene, transportation was never the same. Even so, James J. Hill's vision reached far beyond merely "two streaks of rust" as he changed the world forever.