The Old Broke Rancher Remembers What Going to the Dentist Was Like In His Day

The other day, I took my twelve-year-old to the dentist while I sat in the waiting room and tried to put together one of those Mad Magazine folding puzzles. I almost had it after about forty minutes when the boy resurfaced from the offices. I searched his face for signs of grievous injury.

Once we were in the truck, I said, "how was it, boy?"

He said, "fine, fun, I guess," with a shrug, and that was that. I was positively gobsmacked.

"No trip to the dentist has ever been fun," I protested. "Except maybe for the dentist, if he's some kind of sicko."

You see, I was raised in a deeply Catholic household over which my Mother, God bless her, exercised a domain of pain. How did you know something worked? It hurt. If it hurt, that was a sign that whatever it was, it was working.

When I was little, she brushed my hair like she was a weed whacker and I was a dandelion. If I was unlucky enough to be caught with a little dirt on my face she'd scrub at it like she was trying to get century-old johnny cakes out of a cast iron pan. If I had a little scratch, she'd pour mercurochrome onto it like she was trying to douse a particularly naughty fire.

"Owwwwww," I'd howl.

"It's supposed to hurt," she'd shout over the fracas. "That's how you know it's working!"

Touring the stations of the cross, she'd smile and nod with satisfaction at our savior enduring in extremis. That's how you know the Passion of the Christ was really working, you see.

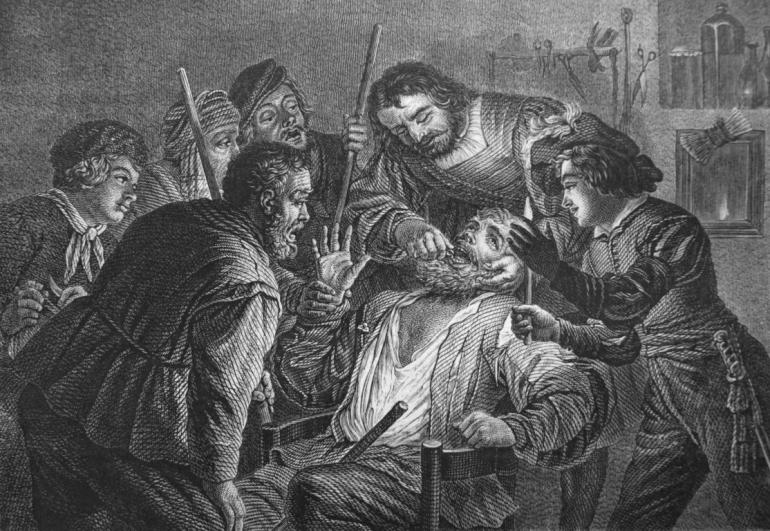

Naturally, therefore, she took me to go see Dr. Rube Wellman, DDS. Dr. Wellman had the distinction of being the oldest living dentist in Montana and possibly the world. He was also legally blind, although Lewistown looked, or rather didn't look, on this fact with a wink. In one year, he managed to get into four car accidents traveling the six blocks between his office and his house.

Now, Dr. Rube was a genuinely kind man, always searching in his white coat for two bits to hand you. Usually, he'd eagerly hand you an ancient horehound or a piece of lint which you'd take with genuine and heartfelt thankfulness, even if you secreted it into the trash can.

But when Dr. Rube was bearing down on you with those boney hands clutching some or another edged weapon, his cloudy, cataracted eyes staring blankly into your tender pink mouth at whatever he could still see there, well, you knew fear.

The next forty minutes to an hour would be Dr. Rube stabbing at your teeth and gums like he was spearfishing and then mumbling half-audible apologies every time he stabbed something soft. Then, mouth plugged with bloody cotton, you'd be ushered back into the waiting room and handed a big sucker. That was how you could tell it worked.

Now my son was telling me that it was fun. He played some video games on a tablet while they looked in his mouth. Then they painted his teeth with something that tasted like bubble gum.

"What, did you sing kumbaya, too? You know, when I was a kid going to the dentist was - "

"I know, it was awful, everything was awful, I'm so lucky, so on."

"The dentist shouldn't be fun. The dentist should be either incompetent or a sadist."

"Maybe you should be a dentist," he quips, the witty little devil.

"Now there's an idea," I said, imagining myself wrist-deep in people's mouths, my unwitting victims unable to escape as I told them one long-winded story after another. Not bad, but I'd rather be a test pilot for a luxury RV company or something.

"Yeah well, I'm glad you're not my dentist, that's for damn sure."

"Why not?"

"Dad, don't you remember when you pulled my tooth?"

This ain't my first rodeo. I've raised four boys, and there might have been a few loose teeth flying around in that time, but I certainly don't remember pulling any.

Now his version of the story is that this was four or five years ago, I was on the couch watching TV, and fixing an electrical plug. I had some tools handy, including a pair of needle nose plyers.

"Show me which tooth", I supposedly said, "and close your eyes, boy!"

Then, if you believe him, I grabbed that sucker with the plyers and yanked it right out of his blessed little head before his mother could come in and kill me for it.

"You glomped onto it."

I said, "Oh come on, I did not."

"Yes you did. The plyers you've got hung up in the shop now."

Now you and I, dear reader, both know full well that my wife would never let me pull a child's tooth with plyers, let alone her youngest baby. I might allow as the fact could cross my mind, as there is indeed a streak of red in my neck. "But your mom would'a never let me pull your tooth with plyers."

He replies, "she was in the kitchen."

"Just because you remember it doesn't mean it happened," I say as if it settled the matter.

But it got me thinking. There was a time when I was exactly the same height as a door knob, and in those days, my grandma certainly took a dally or two with some black thread one of my loose teeth, connected the other end to the doorknob, and exclaimed "look over there!" as she slammed the door shut. About half the time it'd take the tooth out. The other half of the time, it'd just rattle your melon before she'd reset and take another surprisingly forceful swing.

"Alright, so maybe I did pull out your tooth with pliers. I reckon you turned out alright, didn't you? And what your mother doesn't know still won't hurt her."

The next stop, therefore, was another childhood tradition of mine: an after-dentist ice cream excursion, a small kindness observed by my mother, who would take me out for a lime rickey if I didn't make a scene. Now I observe the same tradition. As long as he keeps it secret from his mother

Driving home after he polished off a large chocolate mint malt, he clutched his stomach.

"Ugh, I've got a stomach ache."

"That's how you know it's working," I told him with a wink.