The Old Broke Rancher on Becoming a Hobo at Nine

Graphic by Rob Rath

One summer’s day after church, when I was in first or second grade, one of the big-hatted, blue-haired ladies of the St. Leo’s congregation asked me, within earshot of my father, what I wanted to be when I grew up. I answered, without a moment’s doubt, “I want to be a hobo!” The grand dame’s face colored, but she smiled politely. A few feet away, Dad curled his toes in his boots, trying to hide how embarrassed he was.

“Kids,” he said apologetically.

It seemed an appealing lifestyle to me: they were kings of the road, knights-errant riding iron horses from adventure to adventure. Best of all, they spent most of their time camping and got to eat all the beans they wanted.

My buddy Tom was just as taken with hobo-ing as I was, as I think a lot of boys were in those days. Today, the word is considered pejorative, but we used it with admiration bordering on awe. We knew that many hobos chose the nomadic existence over the more rooted comforts of home. I realize now that most were desperately poor, but we thought they were rich as Croesus.

Our adventure began innocently enough; we had no intention whatsoever of running away. In fact, we had no intention of getting in any kind of trouble at all. But as is so often the case with young boys, we were headed in that direction whether we knew it or not.

It was one of those endless lazy summer days when the sun never seems to set, and Mom and Dad wouldn’t expect us for hours yet, knowing we were up to some mischief at the swimming hole or fishing in our favorite spot on Spring Creek. But we were visiting the local “hobo jungle” at the Milwaukee Rail Yard, just on the outskirts of Lewistown. We liked to listen to their stories, peppered as they were with innuendo and salty language. The stories could be had cheap, offered up for the price of a fresh trout or a bottle of Coke. Our parents didn’t approve, but we figured what they didn’t know wouldn’t hurt them.

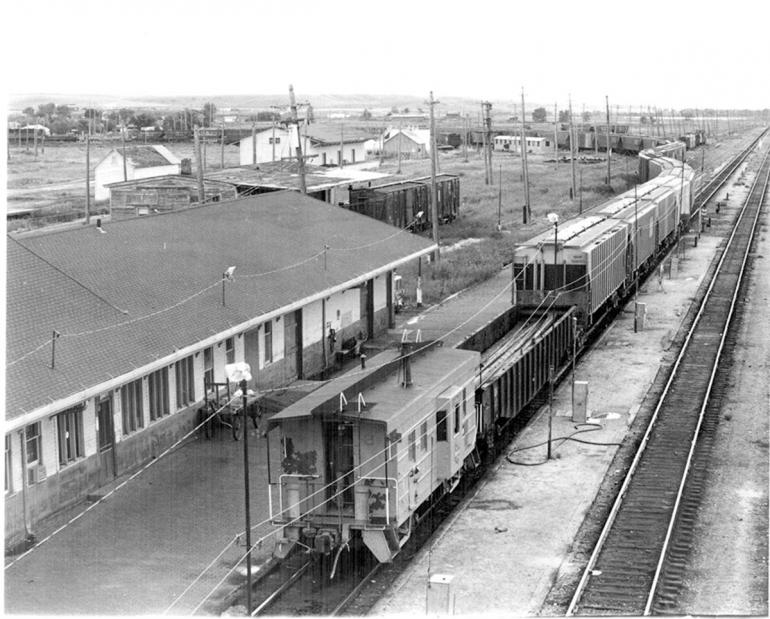

This afternoon there was a stir of activity in the rail yard: a brakeman was walking a cut of cars, lacing up air hoses (that’s railroad parlance) to prepare the train to depart. Nothing unusual, we had seen it lots of times. But, courting inspiration, we hit on an idea: let’s take a short ride as practice for our grownup years hoboing.

Lewistown was not on the mainline. Rather, it ran through Montana a little further south. The big staging yard was in Harlowton, some 70 miles away by train.

If you’re old enough, by the way, you might remember the Milwaukee had electric locomotives to go west, out of Harlowton. It was much more efficient to use electric locomotives with catenary lines to climb over the mountains than the less powerful diesel locomotives; the Milwaukee Road was ahead of its time, but now, like so many things I thought would last forever, it’s gone.

The topography of Lewistown is such that a departing train must circumnavigate what the locals affectionately called Main Street Hill. Anyone entering Lewistown from the west knows her well. You reached a point as you proceeded along the road into town where, suddenly, you were rewarded with a view of paradise on earth, with the Judith Mountains framing the eastern skyline and the little Norman Rockwell town, with its grand courthouse and library and rows of little houses nestled in God’s country like a lamb in a manger.

We thought how fine it would be to survey that vision of heaven from the inside of a train. So we hefted ourselves into the half-open door of a boxcar at rest.

Tom and I calculated that we could hitch a joy ride and jump off before the train left town. In those days, the tracks cut across the whole of Lewistown, so that a long freight train might tie up intersections for miles. We had spent what seemed like hours waited impatiently at crossings, standing beside our bicycles as the big lumbering freight cars trundled their way through town.

What we didn’t realize was the 10 MPH only extended through the crossings, and that as soon as the locomotives went over the last one, they would pick up speed. We also didn’t realize the train we jumped was a little shorter than most. Before we could say “uh-oh,” we were going fast, scary fast, and knew that jumping wasn’t wise. We imagined ourselves pulled under the tracks and flattened like the pennies we had set on the rails for that express purpose.

So we waited, huddled in the boxcar, sitting against unwieldy sacks of gypsum, as the afternoon turned to evening. We listened to the sound of the cars going clickety-clack over the rails, carrying us ever farther from home. There may have been tears. We knew we were in trouble. Eventually, after what might have been countless hours for all we knew, we felt the train slowing.

We had heard stories about the fearsome “Yard Bulls” that stalked the rail cars looking for stowaways. Due to some deficiency of their childhoods, these burly brutes took unwholesome pleasure in beating up the poor innocent hobos. And now that we had unwittingly realized our dream of becoming hobos ourselves, we concluded that we were in for it.

“This here’s a matter of life and death,” Tom told me solemnly. “Whoever or whatever opens that door, we gotta run like hell if we don’t want to get arrested, beat up, or,” and now his eyes narrowed in the darkness, “even shot.”

We pulled into some unknown destination hungry, thirsty, scared, and with no idea where we were. For my part, I thought we could be in Oklahoma or Texas by now.

Then, with a clattering bang, the side door of the boxcar opened, and we found ourselves face-to-face with an enormous simian cranium from which dangled a jowly frown and a cigarette.

“This is it!” Tom hollered, already ducking under the man’s arm and into the night. “Scatter or die, every man for himself!”

Sheer instinct took over. I ran, pumping my arms and legs as fast as they would carry me. In the dim and dusky light, I could just make out a treeline and bolted for it. If I couldn’t be a hobo, I’d be a forest hermit.

To say that big ape was winded when he caught up with me would be an understatement.

Tom was a year and a month older than me, which made him that much more shrewd and elusive, but in the interest of camaraderie, solidarity, or pity, he turned himself in shortly after.

Twisting our ears for making him run for the first time in a decade, the Yard Bull escorted us to his office, interrogated us under hot lights until we gave him our phone numbers, and dialed my house.

I could hear Dad bellowing through the receiver from all the way on the other side of the room.

“They’re where? Harlowton?”

I suppose there was a slight note of relief apparent in his voice, even at that volume, but I’m still glad he had 75 miles of tranquil, scenic driving to cool him off before he picked us up. I counted myself lucky that the Yard Bull hadn’t obliterated us, but I steeled myself for the wrath of an angry father, arguably worse as he was less likely to tan my hide than to say those dreaded words, “I’m disappointed in you, son.”

But it turned out that he was calm by the time he arrived. He even took us to the Tastee-Freez for cheeseburgers and milkshakes before we set out for home.

As we sat in the cab of his truck, he turned to look at me, tousling the hair on my head. “Don’t think this doesn’t mean you aren’t grounded for the rest of your life, boy,” he said with a mouth full of burger.

That only lasted until the afternoon of the next day, at which point he forgot, or at least got irritated at me being underfoot, moping around the house.

Regardless, he sent me out into the golden sunlight to play. And as I dashed down the dirt road to Tom’s house (I had to see how he had fared in his punishment, after all), I was once again daydreaming about the future, plotting once more for a prosperous, fulfilling career as a gentleman hobo.

In that situation, as in others since, if there was a lesson to be gleaned, I carefully resisted gleaning it.

Gary Shelton was born in Lewistown in 1951 and has been a rancher, a railroader, a biker, a teacher, a hippie, and a cowboy. Now he's trying his hand at writing in the earnest hope that he'll make enough at it to make a downpayment on an RV. Hell, scratch that. Enough to buy the whole RV. He can be reached at [email protected] for complaints, criticisms, and recriminations. Compliments can be sent to the same place, but we request you don't send them - it'll make his head big.