Unsolved Montana Murders

Every state has their unsolved murders, of which they are justifiably proud (or is it ashamed?), and Montana is no different. Here, then, are six of Montana’s most enigmatic cases. May they send a wintry chill down your spine, and make you glad of your hot cocoa.

To the extent that it applies: enjoy.

The Disappearance of Father Kerrigan

Late one evening in 1984, Father John Kerrigan, days after arriving at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Ronan, Montana, where he was to be the new priest, went to the local bakery. There he spoke to several acquaintances, members of his congregation. After that, he was never seen, alive or dead, ever again.

Some articles of his clothes, stained with blood, were found along the road. A short while later, authorities found a bloody coat hanger, which was hypothesized to have restrained Father Kerrigan. Then, a week later, his car was found on a country road, the inside splashed with a great deal of blood. Kerrigan’s keys were several feet away, and inside his vehicle they found a shovel, a bloody pillow, and the Father’s wallet, still containing quite a bit of cash.

Since the wallet and cash were still intact, it did not appear that the motive for Father Kerrigan’s murder had been theft, which led investigators to link the crime to another murder of one Father Riviera that had occurred in New Mexico only two days before. Later evidence shed doubt on whether the same killer could have committed both crimes.

The case was even featured on the popular television program “Unsolved Mysteries” in the hope that its millions of viewers could help solve the crime, but to this day there have been no suspects, let alone arrests or convictions. However, one fact which has recently come to light may hold an important clue: in 2015, Kerrigan came posthumously under investigation for sexual misconduct, which might suggest a motive in his murder.

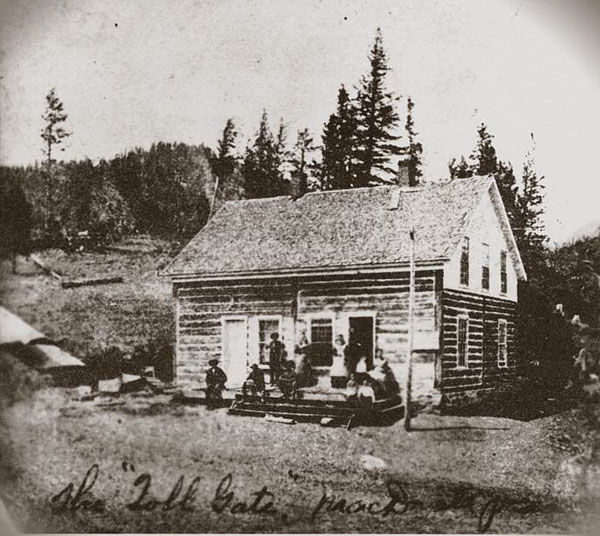

Madame Guyot, in the Mountain Lodge, With a Knife—or a Gun

In 1868, Madame Guyot (history, sadly, does not record the poor woman’s first name), French Canadian, wife of one Constant Guyot, was murdered in her own home or rather, the hostel that she ran, high up in MacDonald Pass. Constant had secured the right to collect tolls on a private road he had built along the Little Bighorn River, which had gained the man some enemies outraged that he was able to collect tolls before the road was even built, including Governor Clay Smith himself.

The road became known as “The Frenchwoman’s Road,” after Madame Guyot, who offered beds and meals for gold dust. Rumors have it that she had managed to ferret away quite a bit of the stuff secret even from her husband.

She was found dead in her lodge; and though initial reports placed the cause of death as a stabbing, it was later reported that she had been shot at close range through her head. Madame Guyot’s belongings were ransacked, her bed opened up with a knife, and her gold dust, if there was any, was gone.

Popular opinion first favored the husband as perpetrator. Constant Guyot had left the house early that morning to tend to a hay field a few miles off, accompanied by a hired hand. Two hours later her body was discovered by a family arriving at the hostel. This would suggest that whoever killed Madame Guyot was lucky in his timing or knew when she was going to be alone.

Murder on the Bozeman Trail

John Bozeman, namesake for the trail and, later, town in Southwest Montana, was many things: a handsome Southern gentleman, unsuccessful business man, successful womanizer, and recipient of a fatal bullet.

He had been on the Bozeman Trail on the way to Fort Kearny in April, 1867, when, according to his travelling companion, Thomas Cover, several Native-Americans approached them. Cover thought they were of the Crow tribe and therefore friendly to white travelers, but after they got close he realized they were hostile Blackfeet. Someone shot first. Bozeman was hit and apparently died instantly, while Cover, wounded by another bullet, shot one attacker and drove off the other. That is, if you believe Cover.

There are those who claim that Bozeman, well-known for his extra-marital conquests, was often more-than-usually proximate to Cover’s wife. One bystander remembered hearing Cover’s wife remark on Bozeman’s looks before they headed out on their final trip together, to which Cover was reported to say “Yes, and take a good look at the son of a bitch, because this is the last you are going to see of him!”

But there are other persistent suspects, too. Like Nelson Story, or rather, a goon pulling a trigger while in the employ of Story. Story was a successful cattle rancher, vigilante and miner, and Bozeman and Cover stayed at Story’s ranch the night before the murder. Seemingly concerned about Native attacks, Story sent Spanish Joe, his colorfully named employee, to investigate the site.

Years later, Story’s son said that his father had told him that Cover had murdered Bozeman by shooting him twice in the back—and shooting himself. Later yet a band of Blackfoot said that they were the ones to kill Bozeman. A dearth of witnesses and conflicting confessions means that we’ll probably never know who really killed the 32-year-old raconteur.

The Mysterious Death of Governor Meagher

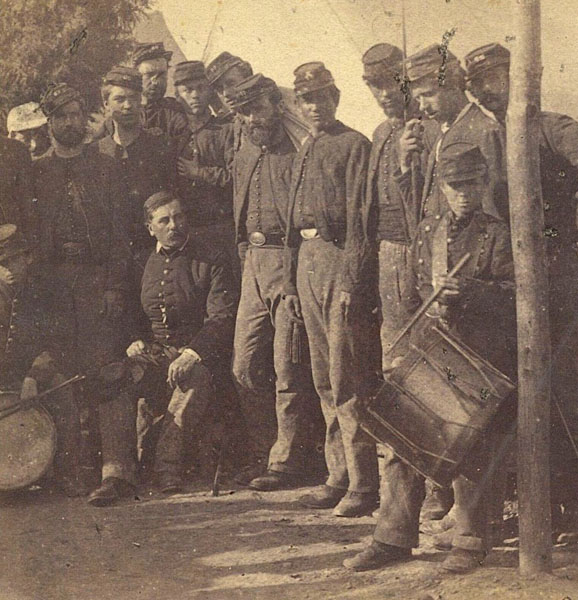

Funny enough, one of Bozeman’s boon companions would also die in 1867, and also under mysterious circumstances. Thomas Francis Meagher is one of the most fascinating and compelling figures in Montana history—and, indeed, 19th century global history.

Born in Ireland, exiled to Australia, he finally immigrated to the United States, where he served as a Union General in the Civil War (distinguishing himself at the battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg) before moving to Montana and becoming Territorial Governor.

It was in his capacity as Governor that Meagher was travelling on a steamboat on the Missouri River. He was on his way to collect a cache of weapons for use by the Montana Militia in retaliation against the Blackfeet for the alleged attack on Bozeman. But, in the days before his arrival at Ft. Benton, he became gravely ill, until early in the first night of July, he apparently fell overboard into the deep, turgid river, never to be seen again.

Even sick, Meagher, a hail and hardy world traveler, was formidably healthy, and almost immediately there were rumors that he hadn’t fallen at all, but been pushed. Some thought it may have been the vengeful act of a Confederate soldier bearing a hateful grudge, or 1867’s most popular scapegoat, the Blackfeet. Others, including writer and Meagher biographer Timothy Egan believe that Meagher was killed by political rivals. But the truth of what happened that evening have long ago been carried down the Missouri and into myth.

The Billings Ax Murders

In December 8, 1924, one of the most brutal and mysterious murders in Montana’s history dominated the front page of the Billings Gazette. “Ax Murders Most Atrocious Crime in History of Billings”, the headline screamed; it continued “Police Cling to Theory of Insane Slayer”.

It seems the only way that the authorities way back then could conceive of a murder as horrible as those of Nels Anderson, a barber, and his wife Anna, was to assume that only a madman could have carried it out.

They were found with their coats and gloves on, as if they were nearly ready to leave their shop. Both had been killed with an ax. Reports emphasize the enormous quantity of blood present at the scene, and yet there was no sign of a struggle. The ax was the Anderson’s own, previously used to cut wood. There was also evidence that the murders were not committed in a rage, but were methodically considered, since fingerprints had been wiped off of the ax handle, and the killer had cleaned his hands (as police assumed it was a man) in a wash basin at the scene.

In the relatively-small community of Billings in the first quarter of the 20th century, it is extremely unlikely that someone could commit a crime of that savagery without being detected. It was therefore assumed that the killer had escaped via the local train, the tracks of which ran very near the Anderson’s shop.

To this day, there have been no suspects in the murders, although unfounded rumors persisted for years, until the crime became, simply, part of Billings history.

Death on the Bad Route

In 1985 Wisconsin man Dexter Stefonek, 67, was driving cross-country on his way back from visiting family in Oregon. His path took him on the perhaps aptly named “Bad Route” road and rest area. All that anyone knew was that Stefonek disappeared, his car was found at the rest area, burned. Then, a short while later, his body was found at the dump, two bullets through his head.

Months later, a tiny piece of graffiti was found in the rest area. A little too profane to reprint here, the grafitti, which seemed to be written in a bragging tone, announced that someone named “Hot Jock” had shot a Wisconsin man. It was therefore assumed that “Hot Jock” was the killer. Police investigated whether “Hot Jock” might be a trucker’s CB handle, and asked for information about men who might go by the moniker, but it failed to produce a suspect. No one has ever come forward with any information.

And yet, as the case is relatively recent at only 35 years old, there is a good chance that someone alive knows what happened to Dexter Stefonek. If that’s the case, there’s still a modicum of hope that Dexter and his family will see justice yet.

If you happen to know anything, please call the Dawson County Sheriff Department at (406) 377-5291.

Montana has one of the lowest murder rates in the Union. In 2015, there were only 36 murders and non-negligent manslaughters in the entire state. Similarly, Montana has one of the lowest rates of unsolved murders as well.

In most of Montana’s communities you can still walk down the street at night without fear of harassment or attack, and folks can sleep soundly in their bed without their front door’s deadlock—or maybe even any lock at all—engaged.

Indeed, Montana’s murders are few, and most of them are, thankfully, solved relatively easily.